Technical SEO is the foundation that ensures your website can be efficiently crawled, indexed, and understood by search engines. If content is king, technical SEO is queen – without a strong technical base, even the best content may fail to rank. This comprehensive guide is tailored for UK businesses of all types – from eCommerce stores and local service providers to B2B companies and SaaS platforms.

We’ll cover core technical SEO concepts and provide practical implementation tips for both Shopify and WordPress websites. You’ll learn how to improve crawlability, indexation, site architecture, mobile optimisation, page speed, structured data, international SEO (hreflang), canonicalisation, duplicate content handling, redirects, XML sitemaps, robots.txt, Core Web Vitals, and even log file analysis. Along the way, we’ll highlight UK-specific considerations such as local SEO for UK regions, preferred tools (with UK support), and legal factors (e.g. GDPR compliance) that may affect technical SEO.

Whether you manage a Shopify eCommerce site or a WordPress blog for your business, this guide offers an intermediate-to-advanced roadmap to technical SEO. We include real-world examples, recommended tools, and case studies to illustrate best practices. Use the structured headings and bullet points to navigate the topics, and feel free to bookmark this as your go-to technical SEO reference. Let’s dive in!

Technical SEO for Different Types of Businesses

Technical SEO principles apply to all websites, but certain nuances differ by business model. Below we outline key considerations for various types of UK businesses:

Ecommerce (Shopify and WooCommerce): Online retailers often have large sites with many product and category pages. Crawl budget management and duplicate content control are crucial – for example, an audit of one UK retail site found over 11 million URLs indexed for only ~160,000 real pages due to uncontrolled faceted filters. Ecommerce sites should use canonical tags on duplicate product URLs (e.g. same product in multiple categories) and ensure discontinued products redirect appropriately. Page speed is critical for conversion, so image optimisation and fast hosting or CDN usage are must-dos. Shopify stores benefit from built-in CDN and sitemap generation, but be mindful of installing too many apps that bloat code and slow pages. Implement Product structured data (price, availability, reviews) to enhance search snippets, and use tools like Shopify’s SEO apps or WooCommerce plugins to manage meta tags and structured data.

Local Service Providers: Local UK businesses (like tradesmen, clinics, restaurants) need to focus on mobile optimisation and local visibility. Ensure your site is mobile-friendly and fast, since many customers find local services on mobile devices. Implement LocalBusiness schema markup with correct NAP (Name, Address, Phone) details for UK addresses and create distinct location or service pages for each area you serve (e.g. “Plumber in Leeds” page). Technical SEO for local sites also means optimising Google Business Profile (although that’s off-page) and making sure your robots.txt doesn’t block important location pages. Use UK map embeds or store locators that do not hinder crawlability. Local sites are often small, but don’t overlook basics like XML sitemaps and indexation – all your service pages should be indexed. If you serve multiple UK regions, consider subfolders or subdomains for each (e.g. /scotland/ vs /england/) and use hreflang if content is region-specific (more on that later).

B2B Websites: B2B companies (e.g. professional services, manufacturers) typically use their websites for lead generation and thought leadership (blogs, whitepapers). Site architecture is key – ensure a logical hierarchy (e.g. Services, Industries, Resources) so both users and crawlers can easily find content. Internal linking should guide visitors to contact or demo request pages, and also distribute link equity to important pages. B2B sites often accumulate lots of content over time, so regularly audit for broken links or orphaned pages. Use canonicalisation to handle duplicated case study content or print-friendly versions. Page speed matters here too – busy professionals won’t wait for a slow site. Implement schema for Articles or FAQs to enhance how your B2B content appears in search. For WordPress-based B2B sites, plugins like Yoast can manage many technical SEO elements (XML sitemap, meta tags, etc.) out of the box.

SaaS Companies: SaaS websites often target international audiences and have unique challenges like user-generated content (forums, support docs) and web applications. It’s vital to separate content meant for indexing (marketing pages, documentation) from the app’s gated areas. Use noindex for app pages or dashboards that shouldn’t appear on Google. SaaS sites frequently have multiple subdomains or domains (for app, blog, help center, etc.), so ensure consistency – all should be on HTTPS and properly linked. International SEO is common for SaaS: if you have a .com serving global users plus a .co.uk for UK, implement hreflang tags to avoid duplicate content across regions. Technical audits for SaaS often reveal issues like duplicate pages (e.g. www vs non-www, or http vs https versions) and missing canonicals – one SaaS case study found critical issues such as duplicate URLs with and without “www”, pages with multiple slashes, missing canonicals, and slow loading pages, all of which were fixed to boost performance. Focus on Core Web Vitals for your marketing site – a fast, responsive site conveys that your product is modern and reliable. Finally, use log file analysis or analytics to ensure crawlers efficiently index your vast documentation or knowledge base without hitting spam or login pages.

No matter your business type, the upcoming sections cover the technical SEO fundamentals every UK website should get right.

How Crawlability Affects Search Engine Indexing

Crawlability refers to search engine bots’ ability to discover and access the pages on your site. If crawlers (like Googlebot) cannot crawl your content, it won’t get indexed or ranked. Key aspects affecting crawlability include your site’s link structure, robots.txt rules, server reliability, and URL parameters.

Check for Crawl Errors: Regularly inspect crawl error reports in Google Search Console and use crawling tools (like Screaming Frog or Sitebulb) to catch issues. Crawl errors occur when a bot tries to fetch a page but fails – common causes are broken links leading to 4xx errors or server issues causing 5xx errors. Fixing these errors is critical. For example, update or redirect broken URLs (404s), resolve server errors, and ensure no essential page consistently times out. Also eliminate redirect loops or chains (multiple hops) which can trap crawlers. A UK case study for a finance website revealed over 26,000 technical SEO issues including masses of 404 errors; once they systematically fixed these, site health improved 22% and organic traffic grew by 45%.

Website Architecture & Internal Links: Good site architecture naturally aids crawlability. Make sure every important page is reachable through internal links (within a few clicks from the homepage). Avoid orphaned pages (pages with no links pointing to them) – these are invisible dead-ends to crawlers. You can use a crawler tool to generate a list of URLs and see which have zero incoming links (Screaming Frog has an “Orphan Pages”). By adding internal links to any orphaned page (for instance, from a relevant hub page or the menu), you integrate it into the crawlable structure.

Use an HTML Sitemap (Optional): Besides an XML sitemap (discussed later), some sites benefit from an on-site HTML sitemap page listing key pages. This can help crawlers (and users) discover deep pages. However, if your navigation and internal linking are solid, an HTML sitemap is optional.

Crawl Depth and Pagination: Ensure that important content isn’t buried too deep. A general rule is that any page should be reachable in no more than 3-4 clicks from the homepage. Deeply nested pages may be crawled less frequently. For very large sites (e.g. ecommerce with thousands of products), implement logical category structures and use pagination with proper tags. Google no longer uses rel="prev/next" for pagination indexing, so each paginated page should have self-referencing canonicals and perhaps links to view-all where feasible. Test that Googlebot can crawl through your pagination by using the URL Inspection tool or a crawler set to simulate Googlebot.

Faceted Navigation and URL Parameters: Many ecommerce sites use faceted filters (by color, size, etc.) which generate myriad URL combinations that can overwhelm crawlers. If your UK online store has such filters, implement controls to prevent crawl traps. Options include using robots.txt to disallow crawling of certain parameter URLs, or adding meta noindex on filter pages, or employing canonical tags to point all variations to a primary page. Be cautious: disallowing in robots.txt will prevent crawling but the URLs could still appear in the “Excluded” section of Search Console if linked; using noindex requires the page to be crawlable to see the tag, so choose strategy wisely. The goal is to avoid wasting crawl budget on pages that add little SEO value (e.g. a filter combination that nobody searches for).

Robots.txt and Crawl Budget: Crawl budget is usually only a concern for large sites, but it’s worth mentioning. Google allocates a crawl rate based on your site’s size and health. If you have tens of thousands of pages, you want Googlebot spending its time on your valuable pages, not endless duplicate or low-value URLs. Later in this guide we’ll cover how to use robots.txt to exclude certain paths from crawling. By fine-tuning what bots crawl, you **preserve crawl budget for important pages. For instance, you might disallow crawling of an /admin/ section or tracking URL parameters. Just be absolutely sure not to block pages that should rank – a small mistake in robots.txt can accidentally deindex your whole site (we’ve seen sites inadvertently disallow “/” which blocked everything!). We’ll dive into robots.txt specifics in a dedicated section.

In summary, to maximise crawlability: fix broken links and errors, maintain a logical link structure (no orphan pages), control problematic URL generators like filters, and use robots.txt carefully to guide crawlers. These steps ensure search engines can freely roam your website’s content.

Managing Page Indexation for SEO

Indexation is the process of search engines storing and including your pages in their search index. After a crawler finds a page, it decides whether to index it (make it eligible to appear in search results). For SEO, we want all important pages indexed, and unimportant or duplicate pages kept out. Here’s how to manage indexation:

Indexability Checks: Use Google Search Console’s Index (Coverage) report to see which pages are indexed, and which are excluded or erroring. The coverage report categorises pages as Valid (indexed), Excluded, Errors, or Valid with warnings. For instance, pages with a noindex tag or duplicate pages that Google chose not to index will show as Excluded. A healthy site shows most key pages as “Valid”. If you notice important pages listed as Excludedor Error, investigate why. Common issues are: accidentally applied noindex meta tags, pages blocked by robots.txt, server errors, or Google considering them duplicates of another URL.

Figure: Google Search Console’s Index Coverage report shows the count of indexed (Valid) pages, and those excluded or in error. A sudden spike in errors (red) or excluded pages can signal technical problems that need fixing.

Maintain an Updated XML Sitemap: An XML sitemap (discussed in detail later) is a file that lists your preferred URLs for indexing. Submitting a sitemap to Search Console helps Google discover new or updated pages faster. It also gives you a way to monitor indexed vs. submitted pages in Search Console. If you see a big gap (many pages submitted but not indexed), that’s a flag to investigate why certain URLs aren’t being indexed.

Use Meta Robots Tags: You have granular control over indexation using the meta robots tag in your HTML. For example: <meta name="robots" content="noindex, follow"> on a page tells crawlers “don’t index this page, but you can follow its links.” Use noindex on pages that you don’t want in search results – e.g. thank-you pages, login pages, internal search results, duplicate pages, etc. One important note: if a page is disallowed in robots.txt, Google might never see the noindex tag on it, so for pages that absolutely must not index, allow crawling but mark them noindex (or use HTTP authentication). On WordPress, SEO plugins let you set noindex on individual pages or entire content types (for instance, many sites noindex their tag archives or filter parameters). On Shopify, you might need a theme edit or app to add noindex tags for certain pages (Shopify now auto-adds noindex to duplicate content like paginated collections or search result pages, but customisation might be needed).

Canonicalisation Signals: Often, we allow Google to crawl many URLs but only want one indexed – canonical tags help with this (see the dedicated Canonicalisation section). Google may choose not to index pages that it considers duplicate or alternate versions, instead indexing just the canonical URL. The Index Coverage report will list these under Excluded (e.g. “Duplicate, submitted URL not selected as canonical”). If you see important pages in that category, double-check your canonical logic.

Managing Index Bloat: Index bloat is when too many low-value pages get indexed. This can dilute your site’s overall quality signals. For UK businesses, index bloat often comes from things like thousands of low-value query parameter pages, printer-friendly duplicates, or archives that aren’t pruned. Use noindex or robots.txt to prevent these from indexing. For example, if you run a UK blog with hundreds of tag pages but each tag page has thin content, consider noindexing tag archives to avoid them clogging the index. In one audit we noted a site had thousands of session ID URLs indexed because the parameter wasn’t handled – a simple fix (adding a canonical or parameter exclusion) can remove those from the index and free up crawl budget.

Fetch and Render: If a page isn’t indexing and you’re not sure why, use the Search Console URL Inspection tool. It will show you if the page was crawled, any blocked resources, and if Google encountered a explicit “noindex” directive. It also shows a snapshot of how Googlebot sees the page. This can reveal issues like a lazy-loading content that never loads for the crawler or a cookie consent interstitial that blocked the content (more on that in the Legal factors section).

Finally, accept that not every page should be indexed. Google often won’t index near-duplicate pages or extremely thin pages. Your goal is to ensure all valuable, unique content is indexed, and to intentionally exclude pages that aren’t useful for search. Regularly review your index coverage: a declining count of indexed pages or a big rise in exclusions can alert you to technical problems early.

Site Architecture and Internal Linking

Your site’s architecture is like the skeleton of a building – it needs to be well-structured so that both users and crawlers can navigate easily. A clear, logical hierarchy and thoughtful internal linking not only improve user experience but also help distribute “SEO equity” (ranking power) throughout the site. Here are best practices for site structure, with examples:

Design a Logical Hierarchy: Organise your content in a hierarchy that makes sense for your business. For instance, an eCommerce site might have Home > Product Categories > Subcategories > Product Pages. A B2B site might use Home > Solutions > Individual Solution Page, etc. Group related content together, rather than scattering them randomly. As an analogy: “You wouldn’t place the pantry and fridge in opposite corners of a house; you’d keep them both in the kitchen. It’s the same with your website – related content should be logically grouped.” This means if you have a section for “Services,” all your service pages should live under that section or menu, rather than being mixed into other sections.

URL Structure: Ideally, your URL structure reflects the hierarchy. For example, www.mysite.co.uk/services/marketing/seo-audit clearly shows that “SEO Audit” is a page under Marketing services. Both users and search engines glean context from such structured URLs. WordPress sites allow pretty permalink structures – use them (avoid IDs or date numbers in URLs for core pages). Shopify uses /collections/ and /products/in URLs by default – that’s fine; just ensure it doesn’t create overly deep paths. Shorter URLs are generally better, but don’t sacrifice clarity. Also, consistency is key: decide if you include a trailing slash or not and stick with it (and redirect the other version) to avoid duplication.

Breadcrumb Navigation: Implement breadcrumbs on your pages, especially if your site has a deep hierarchy. Breadcrumbs (usually at the top of a page) show the path (“Home > Category > Subcategory > Page”) and each part is a link. This not only helps users backtrack easily, but also gives search engines another way to understand your site structure. Google often uses breadcrumb pathways in search result snippets. Both Shopify and WordPress have plugins or built-in options for breadcrumbs (Yoast SEO plugin can add breadcrumbs in WP; many Shopify themes have them or you can code them in). Also mark up breadcrumbs with Schema (BreadcrumbList) for enhanced snippet display.

Strategic Internal Linking: Internal links are a powerful yet often underutilised tool. By linking frequently to your most important pages, you signal their importance to search engines. For example, if you have a high-value landing page (say a product category or a services overview), link to it from your homepage and other popular pages. Use descriptive anchor text that includes relevant keywords (e.g. on a blog post about site speed, link the text “improve Core Web Vitals” to your page speed service page). Avoid overusing exact-match anchors in a spammy way, but be purposeful in linking. If you mention a topic in a blog and you have a pillar page on it, link them. This not only aids SEO but also keeps users engaged by providing pathways to related content.

Avoid Orphaned and Deeply Buried Pages: As mentioned in crawlability, every page should have at least one (ideally multiple) internal link from other pages. Orphaned pages often occur when content is created but not linked in menus or articles (e.g. a new case study put live but not yet added to the Case Studies list page). Use a crawler or SEO audit tool to find orphaned pages and then incorporate them into your navigation or content links. Additionally, flatten overly deep structures. If a user has to click through 5 layers of categories to reach a page, consider adding shortcuts or cross-links. For instance, on an eCommerce site, if products are under Subsubcategory D of Category C of Department B, that’s very deep – you might link to popular products directly from the Category page or homepage during promotions.

Pagination and “View All” Options: If you have paginated listings (like blog archive pages or product category pages), include a “view all” option if it’s reasonable (not too heavy to load), or at least ensure the important items are accessible without needing to page through too much. Also make sure paginated pages link to each other (prev/next links) so crawlers can traverse them all. In WordPress, you might use plugins to control how many posts per page to show (for SEO, more per page can mean fewer pagination pages to crawl, but balance it with page load time).

Hub Pages and Navigation: Create hub pages that consolidate and link out to many sub-topics. For example, a SaaS company might have a “Resources” hub page linking to all whitepapers, webinars, etc., or a travel site might have a page “Browse Destinations” linking to all country pages. These hubs ensure no important page is isolated. Also utilize your footer – linking key pages or categories in the footer provides another route for crawlers (and users who scroll down).

A well-structured site architecture helps search engines understand context and priority. As a bonus, it often earns sitelinks in Google results (indented sub-links) for your homepage, which can improve your result’s prominence. Keep evaluating your structure as you add content – periodically review, and don’t hesitate to re-organise sections if it benefits clarity (just remember to set up proper redirects if URLs change).

Mobile Optimisation

Mobile optimisation is absolutely critical in 2025 and beyond, especially for UK businesses seeing most traffic from smartphones. Google now uses mobile-first indexing, meaning Google predominantly crawls and indexes the mobile version of your site. If your site isn’t mobile-friendly, your search rankings will suffer on all devices. Here’s how to ensure a great mobile experience technically:

Responsive Design vs Adaptive: The preferred approach today is a responsive design – one site that flexibly adjusts layout for different screen sizes. With responsive design, you maintain a single URL per page (no separate “m.domain.com”), which avoids URL duplication issues. All modern Shopify themes and the majority of WordPress themes are responsive out-of-the-box. Ensure any custom CSS you add remains mobile-friendly. The alternative is an adaptive or separate mobile site (e.g. m.yoursite.com), which is generally not recommended unless legacy – it doubles your site versions and requires proper canonical/alternate tags to avoid SEO issues. Responsive is simpler and what Google expects.

In case you do have a separate mobile site for historical reasons, double-check that each desktop page has a corresponding <link rel="alternate" media="only screen and (max-width:...)"> or proper rel=”alternate” and rel=”canonical” tags between versions, though again, a single responsive site is ideal.

Mobile Usability: Use Google’s Mobile-Friendly Test and the Mobile Usability report in Search Console to catch specific issues. Common problems include text too small to read on mobile, clickable elements too close together, or content wider than the screen (requiring horizontal scroll). These are usually design/CSS issues – fixable by adjusting font sizes, button spacing, and ensuring your CSS meta viewport tag is present (<meta name="viewport" content="width=device-width, initial-scale=1.0">). Both Shopify and WordPress handle the viewport tag automatically in themes.

Page Speed on Mobile: Mobile users often have slower connections, so performance is even more important. We’ll cover page speed in the next section, but specifically test your site on a mobile network simulation (tools like PageSpeed Insights let you see mobile 4G/3G load times). Compress images and use lazy loading for below-the-fold images on mobile to save bandwidth. Also minimise heavy scripts – that fancy video background might wow desktop users but could kill mobile performance and data plans.

Optimise for Mobile Interaction: Designing for mobile isn’t just shrinking content – consider how users interact differently on mobile. Mobile visitors are often on the go, looking for quick info and simple navigation. So:

- Use larger, finger-friendly buttons and tappable areas (no tiny text links that are hard to tap).

- Implement sticky elements thoughtfully (e.g. a sticky header or call-to-action that doesn’t occupy too much screen).

- Avoid intrusive interstitials – especially important: Google may penalise sites that show large pop-ups or banners on mobile that cover content (like giant “subscribe now” modals). Cookie banners are allowed but try to keep them small (more on compliance banners later).

- Check that your forms are easy to use on mobile (e.g. use proper

inputtypes for email, number, etc. to bring up appropriate keyboards). - Ensure content isn’t cut off or overlapping due to CSS issues.

As an example of mobile-centric design: a desktop page might show a wide comparison table – on mobile, that might need to scroll horizontally or transform into an accordion list for readability. Test key pages manually on various devices (iPhone, Android, small screen, large screen phones). Emulators and responsive design mode in browsers help, but nothing beats real device testing for quirks.

Mobile Navigation: Many sites use hamburger menus on mobile. That’s fine, but make sure your mobile menu still links to all important sections (don’t hide crucial links). Also ensure that if your desktop site has a mega-menu with many links, the mobile equivalent provides a simple way to reach those links (often via collapsible sub-menus). If important pages are only linked in that mega-menu and your mobile menu omits them, those pages become harder to reach on mobile (and for Google’s mobile crawler).

AMP (Accelerated Mobile Pages): A few years ago AMP was popular for super-fast mobile pages, particularly for news sites. In 2025, AMP is less of a requirement now that Core Web Vitals encourage speed on all pages, and Google has removed the AMP badge. Most UK businesses need not invest in AMP unless they are heavy publishers needing instant load from search/top stories. Focus on making your normal mobile pages fast instead.

In summary, mobile optimisation isn’t a separate task – it should be integral to your design and development process. With most UK internet traffic now mobile (64% by 2025), you must build for mobile first. Google’s mobile-first indexing means any content not visible or accessible on mobile might as well not exist for SEO. So make sure all your key content, internal links, and structured data are present on the mobile view just as on desktop. A mobile-friendly site will please users and search engines alike, driving better engagement and rankings.

Page Speed and Performance

Few technical factors have gotten as much attention in recent years as page speed. Both users and search engines love fast websites. Slow, clunky pages not only frustrate visitors (leading to higher bounce rates and lost sales) but can also hurt your search rankings, as Google uses page speed in its algorithm. Let’s break down how to improve site performance:

Why Speed Matters: Studies consistently show faster sites have better user engagement and conversion. As a famous Amazon statistic goes, every 100ms of latency cost them 1% in sales. Google has likewise found that an increase from 1s to 3s in load time can raise the bounce rate significantly. For UK businesses, this means real revenue impact – especially on mobile connections common in rural areas or on the go. Google has incorporated speed into its ranking “Page Experience” signals, meaning very slow sites may rank lower than their faster competitors (all else being equal).

Core Web Vitals (CWV): These are Google’s key speed and experience metrics, which we cover in the next section in detail. They include loading performance, interactivity, and visual stability measures. Improving general speed usually improves CWV metrics like LCP and FID/INP. So treat Core Web Vitals improvements synonymously with page speed improvements.

Measure Your Speed: Use tools like Google PageSpeed Insights, GTmetrix, or WebPageTest to get a performance report. PageSpeed Insights gives both mobile and desktop scores and specific suggestions (e.g. reduce unused CSS, defer offscreen images, etc.). It also reports field data (from Chrome users) if available, which is valuable for real-world performance. Another tool, Lighthouse, can be run in Chrome DevTools for a quick local analysis.

Optimize Images: Images are often the #1 cause of slow pages. To optimise:

- Compress images (use tools or plugins to reduce file size with minimal quality loss).

- Serve images in next-gen formats like WebP or AVIF, which are much smaller than JPEG/PNG for the same quality. All modern browsers including Chrome, Safari, Edge support WebP; Shopify and WordPress can auto-generate WebP versions (e.g. WordPress does since v5.8+ for images in media library).

- Use responsive images (

<img srcset>attribute) to serve smaller images to mobile devices. This prevents sending a huge desktop-resolution image to a small phone screen. - Implement lazy loading for images below the fold – this defers loading those images until the user scrolls near them. Both WP and Shopify have lazy-load features: WordPress has native lazy loading attribute by default on images, and Shopify themes often include a “data-src” technique or you can add the

loading="lazy"attribute to <img> tags.

Minify and Bundle Resources: Remove unnecessary whitespaces/comments from CSS and JS (minification) to reduce file sizes. Also, combine files when possible to reduce the number of HTTP requests (though HTTP/2 makes multiple requests less costly, combining can still help if you have many small files). For WordPress, caching plugins like WP Rocket, W3 Total Cache, or Autoptimize can minify and concatenate CSS/JS for you. Shopify, being hosted, doesn’t allow installing server-level caches, but you can still minimise custom JS/CSS in your theme and avoid linking too many external scripts.

Use Caching: Enable browser caching with proper cache headers so returning visitors or those clicking multiple pages don’t re-download the same resources. Again, WP plugins handle this easily (and most servers with cPanel allow setting cache rules). On Shopify, static assets are automatically served with long cache lifetimes via the CDN. For dynamic pages, consider a service like Cloudflare to cache and serve pages quickly from a UK edge server, reducing server response time.

Reduce Server Response Time: If Time To First Byte (TTFB) is high, consider your hosting quality. UK businesses should ideally host in UK or Europe for local audience – a server in London will likely be faster for UK users than one in, say, North America, due to lower latency. Ensure your backend (WordPress PHP, Shopify theme liquid, etc.) is efficient. For WordPress, too many slow database queries or an overloaded shared host can slow response. Upgrading to better hosting or using a CDN can mitigate this.

Third-Party Scripts: Be wary of too many third-party scripts (chat widgets, analytics, ads, social media embeds). Each can add network requests and execution time. Audit which scripts are truly necessary. For essential ones, see if you can defer them (load after main content) or use async. For example, a Facebook Pixel or Google Analytics snippet should be loaded asynchronously so it doesn’t block rendering.

Accelerate with CDN: A Content Delivery Network (CDN) like Cloudflare, Fastly, or Akamai can distribute your content across global nodes. For UK sites with mainly UK customers, a CDN with a London PoP (point of presence) will serve content fast to UK visitors and also help international ones by using nearby servers. Shopify uses Cloudflare under the hood for static assets. WordPress users can integrate CDNs easily via plugins or services (Cloudflare has a free tier that works well for many).

Profile and Benchmark: If you want to go deeper, use performance profiling tools. Lighthouse (in Chrome devtools) has a performance tab showing where time is spent (scripting, rendering, etc.). This can identify, for example, a particular script that is a bottleneck. For advanced analysis, something like Google’s Puppeteer or WebPageTest’s filmstrip can show load progression. But for most, the PageSpeed Insights recommendations are a great to-do list.

Keep in mind that speed improvements often involve diminishing returns – fix the big stuff (huge images, lack of caching, slow server) before chasing every last millisecond. Aim to be faster than your key competitors. A practical target is to have your pages consistently load in under 2-3 seconds on mobile 4G and under about 1.5 seconds on desktop broadband for the main content. And ensure your site feels responsive (which ties into interactivity metrics we’ll discuss next).

By making performance optimisations, you not only boost technical SEO but also user satisfaction. Faster sites tend to get higher conversion rates – a win-win scenario. Next, we’ll look at Core Web Vitals, which zero in on some specific aspects of page experience beyond raw speed.

Core Web Vitals (Page Experience Metrics)

Google’s Core Web Vitals are a set of user-centric performance metrics introduced to quantify aspects of page experience. As of 2024/2025, they have become key indicators and ranking factors under Google’s “Page Experience” update. For UK site owners, understanding and optimising these metrics can help improve both rankings and user happiness. The three Core Web Vitals (CWV) are:

Figure: Google’s Core Web Vitals metrics – Largest Contentful Paint (LCP) for loading, Interaction to Next Paint (INP)for interactivity (recently proposed to replace First Input Delay), and Cumulative Layout Shift (CLS) for visual stability. The thresholds above show what is considered “Good” (green), “Needs Improvement” (amber), or “Poor” (red) for each metric.

- Largest Contentful Paint (LCP): This measures loading performance – specifically, the render time of the largest image or text block visible within the viewport, relative to when the page started loading. In simple terms, it gauges how quickly the main content appears. Goal: LCP under 2.5 seconds is considered good. For example, on a blog page the LCP might be the article’s banner image or the first heading text; on an eCommerce page it could be the main product image. To improve LCP: optimise server response, use a CDN, compress and preload important images, and remove render-blocking elements that delay the main content.

- Interaction to Next Paint (INP): INP is an experimental metric (likely to replace First Input Delay) that measures responsiveness – it looks at the time from a user’s interaction (like clicking a button) to the next time the page updates (e.g. shows a response). Essentially, it evaluates if the site quickly reacts to user input. Goal: INP under 200 milliseconds is good. Long INP often indicates heavy JavaScript keeping the main thread busy. To improve INP: minimise long JavaScript tasks, break up heavy JS work, and use browser APIs that enable smoother interactions (like

requestIdleCallback). For now, Google still reports First Input Delay (FID) in Search Console which requires <100ms for good – focusing on INP means aiming for similar speedy interaction. - Cumulative Layout Shift (CLS): This measures visual stability – how much the page’s layout moves around during load. You’ve probably experienced going to tap a link and the page shifts and you click the wrong thing – that’s what CLS captures. It’s calculated based on the fraction of the screen that shifts and the distance of shift. Goal: CLS below 0.1 is good. Common causes of poor CLS are images or ads without dimensions specified (causing popping in), or late-loading fonts that change text size, or inserting DOM elements above existing content. To improve CLS: always include width/height attributes or CSS aspect ratios for images and video embeds, reserve space for ads or embeds via CSS min-height, and use

rel="preload"for critical webfonts so they load earlier (or use font-display: swap so text shows with a fallback font rather than invisible).

Google considers these metrics crucial because they reflect real user experience. In Search Console’s Page Experience(Core Web Vitals) report, you can see what percentage of your pages are passing CWV for real users (data from Chrome User Experience Report). If you find some URLs failing, focus your optimisation there.

Improvement Strategies: Many improvements overlap with general speed:

- For LCP: Ensure the server responds quickly (maybe implement caching for HTML or faster hosting), and that the largest element loads early. Using the

<link rel="preload">on your hero image or critical banner can hint to the browser to fetch it sooner. - For INP/FID: Reduce third-party scripts and heavy JS. Also, code-split or defer non-critical JS so the page becomes interactive faster. If using WordPress, audit your plugins – some plugins load heavy scripts on all pages. Maybe remove or replace bloated plugins.

- For CLS: Identify any unstable elements. You can add a temporary outline to all elements while testing to see what jumps. Common fixes include adding explicit size attributes to images (so the browser reserves the space), and avoiding dynamically injecting content above existing content. If you have a cookie consent banner appearing at top, that can push content – instead, show it as a slide-up from bottom or an overlay to avoid layout moves.

Monitoring: After making changes, re-test with PageSpeed Insights or the Core Web Vitals report. Note that field data (what Search Console shows) can take a couple of weeks to reflect improvements, as it’s based on rolling data from users. For immediate feedback, rely on lab tools like Lighthouse and Chrome’s developer tools performance panel.

Core Web Vitals are not UK-specific – they apply globally – but one UK consideration is connectivity. Users in different parts of the UK (rural vs urban) may have varying network speeds; optimising for slightly lower-bandwidth scenarios can be beneficial. Also, consider that a large portion of mobile users could be on less powerful devices – so optimizing JS helps a budget Android phone user even more than an iPhone user.

In summary, treat Core Web Vitals as an ongoing KPI for your site’s technical health. Google’s thresholds (LCP <2.5s, INP/FID <0.2s/100ms, CLS <0.1) are minimum targets; beating them by a margin provides a buffer. UK businesses that prioritise CWV have a competitive edge in SEO and deliver a noticeably better user experience, which in turn can improve engagement and conversion. It’s truly a case where good SEO is good UX.

Structured Data and Schema Markup

Structured data (Schema.org markup) is a technical SEO component that can give your site an extra advantage by enhancing how your listings appear in search results. By adding special HTML annotations (often in JSON-LD format) to your pages, you help search engines understand the content in a more nuanced way, enabling rich results like star ratings, product prices, FAQ dropdowns, and more. For intermediate/advanced users, structured data is a must-have for standing out on crowded SERPs.

What is Schema Markup? It’s a standardized vocabulary (Schema.org) that you can embed in your page code to define the type of content. Think of it as adding “tags” that explicitly say “This page is a Product, its name is X, price is £Y, and it has 4.5 stars from 20 reviews.” Or “This page is an Article, with author Jane Doe and publish date…”. Search engines parse this and can present the info directly in results. It doesn’t directly boost rankings by itself, but rich snippets can improve click-through rates, and providing structured data helps search engines index and present your content better.

Common Schema Types for Businesses: There are hundreds of schema types (currently over 800), but some of the most relevant for UK businesses include:

- Organization schema for your company (name, logo, contact info, social profiles).

- LocalBusiness schema for local companies, including address (with proper postal code format), opening hours, geo-coordinates, etc. This can enhance your presence in local searches.

- Product schema for eCommerce product pages – includes name, description, price (use GBP currency code), availability (InStock/OutOfStock), brand, SKU, and aggregate rating if applicable. When done right, Google can show price and stock info in the snippet.

- Review/Rating schema – often combined with Product or placed on testimonial pages to display star ratings.

- Article/BlogPosting schema for content articles and blogs (helps Google understand author, publication date, etc., and enables things like carousel features for news).

- FAQPage schema for pages that are in Q&A format. If you have an FAQ section on a page, marking it up can get you a rich snippet with expandable questions directly under your Google result.

- Breadcrumb schema to mark up breadcrumb navigation (Google often displays breadcrumb paths instead of full URLs in results).

- SoftwareApplication schema for SaaS products might be used to indicate software details (useful if you want to appear in Google’s software platform listings).

- Event schema if you run events/webinars, etc.

- VideoObject if you have videos embedded, which can help them appear with a thumbnail in results or in Google Video search.

Choose schema types relevant to your content. Don’t overdo it or mark up content that isn’t visible or doesn’t exist (that violates guidelines).

Implementation on Shopify and WordPress:

- Shopify: Many Shopify themes come with basic Product schema out of the box. Check your page source for

<script type="application/ld+json">blocks. If your theme lacks certain schema (like Article for blogs or Breadcrumbs), you can edit the theme code to add JSON-LD. There are also Shopify apps (e.g. “JSON-LD for SEO”) that can automate adding comprehensive schema markup site-wide. As of recent Shopify updates, they even auto-inject some Organization data. Always test after changes. - WordPress: SEO plugins like Yoast SEO or RankMath make schema easy. Yoast automatically adds Organization or Person schema (based on your settings), breadcrumbs schema if you use Yoast breadcrumbs, Article schema for posts, etc. You can also use dedicated schema plugins (like Schema Pro or WP Schema) to add custom schema types via GUI. For example, adding FAQ schema to a page is as simple as filling a form in some plugins. If coding manually, you can paste JSON-LD in the HTML (preferably in the head or near bottom of body). JSON-LD is Google’s recommended format (versus inline microdata) because it doesn’t affect the visible page elements and is easier to manage.

Validation and Testing: After adding structured data, use Google’s Rich Results Test tool to verify it’s working. This online tool will tell you which schema it detects on the URL and if it’s eligible for rich results. It will flag errors or warnings – e.g. if a Product schema is missing a required “price” field, or if your FAQ schema text doesn’t exactly match visible text (they check for consistency). Fix any errors. Warnings (like “image field is recommended”) are optional but consider adding those for completeness.

Also, Search Console has a Rich Results Status (under Enhancements, e.g. “Products”, “FAQ”, etc.), which shows how many pages’ markup is valid or has errors. Keep an eye there after deployment.

Stay Up to Date: Schema is ever-evolving. New types or properties get added as search features expand. For instance, with the rise of AI and voice search, types like HowTo or Speakable for news articles have emerged. Keep an ear on Google Search Central blog for announcements of new supported schema. Being an early adopter (when relevant) can give an edge. For example, when Google enabled FAQ schema in results, websites that quickly added it enjoyed larger SERP real estate. (Do ensure your FAQs are truly useful; Google may not show the snippet if it thinks it’s not helpful or if it appears spammy).

Don’t Misuse Schema: It’s important to follow Google’s guidelines: the schema data you provide must match what’s visible on the page. No inventing 5-star “reviews” just to get stars, unless those reviews actually exist on the page. Google does manual and automated checks for schema spam, and penalties can be applied for structured data abuse. A notable UK example was the travel site that got a manual penalty for marking up unrelated content as FAQ just to gain snippet space – not worth it. Be honest and accurate with your markup.

When properly used, structured data can lead to rich search results that attract more clicks. For UK e-commerce in particular, showing prices and stock in SERPs can draw in ready-to-buy customers. Local businesses might see a knowledge panel enhancement if organization markup is present. In summary, schema markup is a technical enhancement that can set your site apart – implement it wherever applicable, and test it to ensure it’s error-free.

International SEO (Hreflang)

If your business targets multiple countries or languages – for example, a UK company also serving customers in Ireland or an English site with variations for French or German markets – international SEO comes into play. The hreflang attribute is a technical markup that tells Google about alternate versions of a page for different languages or regions. Implementing hreflang correctly can prevent duplicate content issues across regions and ensure users see the version of your site meant for them.

What is hreflang? It’s an HTML attribute (placed in either <head> tags or in sitemaps) that specifies the language and optional region of a URL’s content, along with its alternate equivalents. For instance, on your UK English homepage, you might include:

<link rel="alternate" hreflang="en-gb" href="https://www.example.com/uk/">

<link rel="alternate" hreflang="en-us" href="https://www.example.com/us/">

<link rel="alternate" hreflang="x-default" href="https://www.example.com/">This tells Google “We have versions of this page for English-UK and English-US, and perhaps a default catch-all.” Google will then try to show the UK page to UK users, the US page to US users, etc. This avoids scenarios like a UK searcher landing on your US site version or vice versa.

When do you need hreflang? Only when you have truly equivalent pages targeted to different locales. If your site is solely for the UK and nowhere else, you don’t need hreflang. But if you have, say, a .co.uk site for UK and a .com for international, or a multi-language site (English, French, etc.), you should use hreflang. Even within English, UK vs US or CA (Canada) differences matter – perhaps pricing in £ vs $, spelling differences (optimisation vs optimization), legal terms, etc. Hreflang handles cases where content is similar but intended for different audiences.

Implementation Methods: There are three ways to implement hreflang:

- HTML

<link>tags in the page head (as shown above). Each page lists itself and all its alternates. - XML sitemap entries with

<xhtml:link rel="alternate" hreflang="...">for each URL and its alternates. - HTTP headers (least common, mostly for non-HTML files).

Most opt for method #1 or #2. If you have a relatively small number of language versions, head tags are fine. If you have a huge site with many language versions, maintaining hreflang via sitemaps might be easier (and keeps HTML cleaner). Crucial: Hreflang annotations must be bidirectional (reciprocal). If page A says page B is its hreflang alternate, page B must also list page A. Missing return tags is a common mistake that can invalidate your hreflang signals.

Language vs Region Codes: hreflang="en" alone means any English. You can specify region like en-gb for English (Great Britain) and en-us for English (United States). For UK targeting, use en-gb (GB is the ISO country code for United Kingdom). If you had a French page for Canada, it’s fr-ca versus French for France fr-fr. Use language codes per ISO 639-1 and country codes per ISO 3166-1 Alpha 2. Note: If language is the same and only region differs but content is identical, some sites choose not to bother splitting (but often there are differences like currency, so typically you do separate).

Hreflang on Shopify and WordPress:

- Shopify – If using Shopify’s multi-language feature (available to Shopify Plus or via certain apps), Shopify can automatically generate hreflang for different language versions of products/pages. If you have separate Shopify stores for different countries (e.g. one store for UK, another for US), you’ll need to manually add hreflang or use apps that coordinate between stores. Shopify doesn’t have a built-in hreflang manager across stores out of the box.

- WordPress – Plugins like WPML (for multi-language content) handle hreflang for you. If you run separate sites, you might use a plugin like “Hreflang Manager” or add code in functions.php to output hreflang tags in the head. There are also SEO plugins (Yoast premium has some hreflang support when using WPML). Ensure each page’s alternates are correctly mapped.

Avoid Duplicate Content Issues: A fear site owners have is that having similar content on a .co.uk and .com might trigger duplicate content penalties. Hreflang largely mitigates this by telling Google these are intended alternates, not trying to spam the index. Google will typically choose one version to show per user location/language. However, do localise content where possible. Even changing currency symbols (like £ vs $), spelling (colour vs color), or slightly adjusting messaging for the market can improve user resonance and also differentiate the pages a bit.

x-default: Include an x-default hreflang value if you have a default page that isn’t specifically targeted. Often the global homepage (like .com default) is marked x-default to catch users who don’t fit other rules. It’s optional but recommended if you have a page meant for “rest of world” or a language selector page.

Testing hreflang: Use Google’s hreflang testing tools or third-party tools like Merkle’s hreflang validator. They will check that all reciprocals are in place and that codes are valid. Also, monitor in Search Console’s International Targetingsection (note: Google deprecated the old report in 2023, but you can still see hreflang issues as messages or in the Index Coverage if something’s off). If Google detects improper hreflang (like inconsistent pairs or unknown language codes), they might ignore it.

Example Case: Suppose you run a SaaS with an English website but have a significant customer base in Germany, so you create a German-translated site section. You’d add hreflang tags on English pages pointing to the German versions (hreflang="de"), and vice versa. This way a German user searching will be served the German page, not the English one. If you didn’t do this, Google might still figure it out by language, but with hreflang you’re explicitly guiding it. Also, if content is similar, hreflang prevents Google from thinking it’s duplicate spam.

For UK businesses expanding abroad or vice versa, hreflang is vital for a smooth international SEO strategy. It ensures each audience finds the most appropriate content. Implement it carefully as mistakes can be tedious to debug. But once it’s correct, it’s largely a set-and-forget aspect of technical SEO that yields long-term benefits in user satisfaction and regional search performance.

Using Canonicalisation to Control Duplicate Content

Canonicalisation is the practice of specifying the “preferred” version of a page when multiple URLs have the same or very similar content. In essence, you’re telling search engines: “If you find this content at different URLs, please treat this URL as the primary one.” This is done via the canonical tag and is crucial for controlling duplicate content and consolidating ranking signals.

The Canonical Tag: A canonical tag is a simple HTML link element placed in the <head> of a page:

<link rel="canonical" href="https://www.example.com/preferred-page-url" />If a page is the preferred version of itself, it should canonicalize to itself (self-referential canonical). If it’s a duplicate or variant, it should point to the main URL. Search engines then attempt to index and rank only the canonical URL, ignoring the duplicates in the results. Note that canonical is a hint, not a directive – Google usually respects it but may ignore it if it thinks you made a mistake or are trying to game the system.

Use Cases for Canonicalisation:

- WWW vs non-WWW, HTTP vs HTTPS: Typically you redirect one to the other, but canonical tags on pages can double confirm. If someone manages to access the wrong version, the canonical tag will point to the right one.

- Faceted and Sorted Pages: Suppose on an eCommerce site you have

?sort=price_ascor filter parameters. Ideally, you canonical those to the base category URL (without parameters) if the content is basically the same items just sorted differently. - Mobile vs Desktop URLs: For sites still using separate m. mobile sites, each desktop page should canonical to itself, and the mobile page should canonical to the desktop (and use alternate tag for mobile). But in responsive setups, this is not an issue.

- Session IDs / Tracking Parameters: Often, users might land on URLs with session or affiliate IDs (e.g.

?utm_source=...). These create duplicates. Implementing a canonical to the base URL ensures Google ignores the tracking version. Many CMS do this by default (e.g. Yoast SEO adds a self-canonical to WP pages, which naturally causes any parameterized version to point to the original). - Print or AMP pages: If you have a printable version of an article at

...?print=true, canonical it to the main page. Similarly, if using AMP (Accelerated Mobile Pages), the AMP page has a canonical pointing to the main page, and the main has an amphtml link to AMP. - Duplicate content across sites: If you syndicate content or have the same article on two of your domains, you could canonical one to the other, but note that canonical tags only work within the same site owner scope typically (cross-domain canonicals are possible, but both sites need to be yours and it’s a bit advanced).

Shopify & WordPress specifics:

- Shopify automatically adds canonical tags on collection and product pages, usually pointing to the primary URL without any query strings or pagination. For example, page 2 of a collection might canonical to page 1 (this is debated since page 2 has different items – some Shopify themes now treat page 2 as a separate content and self-canonicalise it). Be aware of how your theme handles this. Also, Shopify by default canonicals product variant URLs to the main product URL.

- WordPress with Yoast will output a self-canonical on every page by default. If you need to override (say you have a paginated series or an alternate page), Yoast Premium or other plugins allow specifying a custom canonical. If not using a plugin, you might add a

<link rel="canonical">in your theme header manually for specific templates.

Duplicate Paths Example: A common issue is the same page accessible via multiple paths. For instance, your site might allow /category/page and also /page (if a page is in one category but also accessible at root). This can happen with WordPress if not configured properly or with certain plugins. Using a canonical on /page to itself ensures if Google finds /category/page, it knows to index just /page (also better to fix the URL routing if possible).

Parameter Handling: Google Search Console had a URL Parameters tool (deprecated now in 2022/2023), which let you indicate how to handle certain params. Without it, canonicals and robots.txt are your main tools. If a parameter doesn’t change content (like ?ref=facebook), Google usually figures it out and clusters those URLs under one canonical on its own, but providing explicit canonical is safer.

Rel=”alternate” vs Canonical: One should not confuse hreflang alternate with canonical. If content is truly the same and meant to be one page, canonical is used. If content is meant for different users (like language variants), use hreflang and do not canonical them together (that would tell Google to ignore one). For example, don’t canonical your US page to your UK page even though they’re similar; use hreflang. Canonical is for duplicate content consolidation.

Not a Directive: Google may ignore canonicals in some cases. For example, if you canonical every page of your site to the homepage (please don’t!), Google will ignore that and treat it as a mistake. Or if you have two pages that aren’t identical and you canonical one to the other, Google might still index both if it finds them sufficiently different or each with unique signals. Canonical works best for clear duplicates or very close copies.

Monitor in Search Console: If Google chooses a different canonical than you specified, it’ll show in Index Coverage reports (e.g. “Indexed, not canonical” or “Duplicate, Google chose different canonical”). That’s a sign something’s off – maybe the pages aren’t as duplicate as you think, or maybe your internal linking is all pointing to the non-canonical version, confusing Google. Adjust accordingly (either change canonical strategy or unify content).

UK Specific Domain Canonicalization: If you changed your primary domain (say from .co.uk to .com post-Brexit for a broader audience), ensure all pages canonical to the new domain and that old pages redirect. Another scenario: some UK sites use both .co.uk and .com (one might redirect to the other, or one for UK one for global). If for some reason you keep both live with similar content (not ideal), you can canonical the .com pages to .co.uk for UK content – but it’s usually better to just fully separate or redirect.

In summary, canonical tags are your friend in managing duplicate content. They help consolidate SEO value (links, content signals) to the main version of a page rather than splitting among duplicates. Use them thoughtfully: when you intentionally have multiple URLs for the same content (which often happens beyond our control), canonical tags keep your SEO streamlined by pointing to the primary URL. This way, search engines won’t be “unsure which page to display” and risk splitting rank – you’ve given them a clear instruction.

Duplicate Content Management

Duplicate content can be a thorn in the side of many websites. From an SEO perspective, duplicate content is problematic because search engines don’t want to show multiple identical (or very similar) pages in results, and it can dilute your ranking signals. “Duplicate content” can refer to on-site duplicates or content that’s duplicated on other sites. Here we focus on on-site (technical) duplicates and how to handle them for UK businesses.

Common Causes of Duplicate Content:

- URL variations: as discussed, the same page accessible via different URLs (with/without

www, HTTP/HTTPS, trailing slashes, parameters, session IDs, etc.). - WWW vs non-WWW, .co.uk vs .com: If both versions are live without proper redirects, that’s full duplication of the site. The best practice is to 301 redirect one to the other (and inform Google in GSC of your preferred domain historically, though that feature is gone now – but a 301 and consistent linking suffice).

- Printer-friendly pages or alternate format pages: e.g.

example.com/pageandexample.com/page?print=1show the same content. Or a web page vs PDF version of a report. - Faceted navigation: filtering can produce pages that overlap significantly in content (e.g. “red shoes size 9” vs “red shoes size 10” – mostly same products). If each filter combo has a URL and is indexable, you have lots of near-duplicates.

- Pagination & Sorting: A category sorted by price low-to-high vs high-to-low contain same items, just order differs. Those pages are technically duplicates content-wise.

- Boilerplate repetition: Large header or footer sections repeated can make pages appear duplicate to algorithms if the unique content is minimal in comparison. Ensure each page has enough unique text.

- Copied or template text: If a multi-location business has 10 location pages with almost identical content except the city name, that’s duplicate content. This is common (e.g., “We offer plumbing services in [London]” vs “…in [Manchester]”). It can hurt both pages. The fix is to differentiate those pages with truly local content (talk about the area, specific projects there, testimonials from local clients, etc.) or consolidate if not needed.

Why It Matters: Google generally does not penalize duplicate content (unless it’s spammy or deceptive), but it will choose one version to index and ignore others. You might not control which one it picks unless you guide it. For instance, if your homepage is accessible at /?ref=twitter and gets indexed instead of clean /, that’s messy. Also, duplicates split link equity – some sites linking to one URL, some to the other – if not consolidated, no single page gets full credit. In the Very.co.uk case study we cited, they had massive content duplication and Google indexed millions of pages, hurting crawl efficiency. Resolving duplicates helped them regain control and boost rankings.

Solutions Recap:

- 301 Redirects: If a duplicate is not needed, simply redirect it to the main version. Ex: force all traffic from

http://tohttps://, from old URLs to new, etc. Redirects are a strong signal to search engines. - Canonical Tags: For cases where you keep multiple versions accessible for users, canonical is the solution (as detailed earlier). Ex: keep print page for user convenience, but canonical it to main page.

- Meta Noindex: For duplicates that serve a purpose for users but you don’t want indexed at all (like internal search results pages, which often produce duplicate/already-indexed content combinations), you can noindex them. Ex: a search result for “product X” often duplicates the product page content – better to noindex site search pages.

- Consistent Linking: Choose one URL format as the standard (the canonical one) and always link internally to that. E.g., ensure your navigation links to

https://www.site.com/pageconsistently, not mixinghttp://or non-www. If you have tracking parameters for some links, use ones that don’t affect content or use the parameter in a way that Google can ignore it (like putting it in fragment #, though that’s not usable for server-side). - Differences for Similar Content: If you have similar pages, make them more unique. For example, an online retailer might have multiple pages for the same product if it’s in different categories – that’s a use case for canonical to one primary product URL. But if you have similar products (blue shirt vs red shirt pages) that are distinct products, that’s fine. Ensure each has unique description (don’t copy-paste the manufacturer description everywhere – add original content).

- Hreflang vs Duplicate: Multi-region duplicates, as mentioned, handle with hreflang. Don’t noindex or canonical your UK site to your US site – keep both, differentiate where you can (currency, language nuance), and use hreflang so they aren’t seen as competing duplicates but rather alternates.

Duplicate Content Tools: Tools like Siteliner or Screaming Frog SEO Spider (which has a duplicate content report by comparing pages’ content hashes or titles) can identify internal duplicates. Google’s Index Coverage might show “Duplicate without user-selected canonical” indicating it found two similar pages and chose one to index. Also, simply searching for a chunk of text in quotes on Google can show if multiple pages from your site appear for it.

Thin Content Overlap: A related issue – if you have many pages that aren’t exactly duplicates but very thin and similar, consider consolidating them. For instance, a blog with 50 posts each 100 words on very similar topics could be merged into a few comprehensive posts. Thin, near-duplicate pages can drag down a site’s perceived quality. The Panda algorithm historically targeted that. If you identify such cases, either beef up their content or noindex/remove them.

External Duplicate Content: If you supply content to other sites (e.g. guest posts, press releases) or have content scraped, use canonical or at least ensure you are identified as the original. You can ask scrapers to add a canonical pointing to your version, though that’s often not feasible. But this veers into content strategy rather than site technical structure.

For UK business sites, a typical duplicate issue might be something like having a separate mobile site, or inadvertently having both example.co.uk and example.com live with same content. Always audit after any platform change or migration – test a few pages by appending random parameters, uppercase vs lowercase in URL, etc., to see if they resolve to one version.

By diligently eliminating or consolidating duplicates, you make your site more efficient for search engines and strengthen the SEO of your key pages. As the saying goes in SEO, “Don’t compete with yourself.” Each distinct piece of content should have one URL to rule them all – use the techniques above to ensure that’s the case.

Redirects and URL Changes

Redirects are an essential technical SEO tool for managing URL changes and ensuring users and search engines get to the right content. A redirect sends both browsers and bots from one URL to another automatically. They are commonly used during site migrations, URL restructuring, or to clean up outdated content. Let’s cover best practices for redirects, particularly focusing on SEO impacts:

Types of Redirects: The two main HTTP status codes for redirects are:

- 301 Permanent Redirect: Signals that a page has moved permanently to a new URL. This is the most SEO-friendly for permanent moves because search engines pass the majority of the original page’s ranking power (link equity) to the new URL. Always use 301 for content that’s not coming back.

- 302 Found (Temporary) Redirect: Indicates a temporary move (the original may come back). Search engines typically do not transfer long-term ranking to the new URL (they may still index the original if they think the move is temporary). Use 302 if you truly intend to bring the old URL back or for short-term reroutes (like A/B test or a maintenance mode).

- Less common: 307 (HTTP/1.1 temp redirect), 308 (permanent similar to 301), but 301/302 cover most needs.

When to Use Redirects:

- Site migration (domain change): e.g., moving from

oldsite.co.uktonewsite.co.ukor .com. You should implement a one-to-one 301 redirect from every old URL to its corresponding new URL. This preserves your SEO rankings as much as possible. Google will over time treat the new URLs as replacements, especially if all content stays same. - HTTPS upgrade: if you move from http to https, you must redirect http to https site-wide (and update canonical tags accordingly). Today, having a site not on https is rare (and not recommended, since it’s a ranking factor too).

- Removing or renaming pages: If you discontinue a service or product page, and there’s a closely related page (like a newer model, or a category page), 301 redirect the old URL there. If there’s no equivalent content, you might choose not to redirect and let it return 404 or a “410 Gone” (410 explicitly says the content is gone and not coming back, which can sometimes drop it from index faster). But generally, if an old URL had any links or traffic, capture that via a redirect to the nearest relevant page.

- Consolidating content: Merging two blog posts into one? Redirect the weaker one to the combined version. Changing URL slugs for better technical SEO? Redirect the old slug to the new one.

- Trailing slash or case normalization: Some sites choose to redirect

/pageto/page/or vice versa for consistency. Also redirecting any mixed-case URLs to lowercase if your system treats them the same. (This is often handled at server or CMS level automatically). - Canonical issues fallback: If despite canonical tags, you find Google indexing a duplicate URL, you could add a redirect from the unwanted URL to the canonical one to force the issue.

Avoid Redirect Chains: A redirect chain is when URL A -> B -> C (multiple hops). This can slow down crawling and dilute link equity transfer (Google says it will still pass PageRank through up to several hops, but user experience suffers). If you redesign and then redesign again, update any old redirects to point directly to the final destination. For example, if page1 -> page2 (set last year) and now page2 -> page3 (new), it’s better to adjust the first redirect to go straight to page3 then remove the intermediate step.

Update Internal Links: Ideally, once you put redirects in place, also update your site’s internal links to point to the new URLs directly, rather than relying on the redirect. This reduces load and ensures crawlers see a clean architecture. It’s common after a migration to do an internal link audit and replace old URLs in menus, sitemaps, etc., with the new ones.

Handling 404s: Not every 404 needs a redirect – only if there’s a relevant page to send users to. If someone hits a completely non-existent URL (typo or something), serve a helpful 404 page (with search bar, popular links). Use Google Search Console’s crawl error report to see if certain 404 URLs are getting hits – if you find many hits on a particular retired URL, maybe that merits a redirect to something useful rather than leaving visitors at a dead end.

Redirects on Shopify and WordPress:

- Shopify has a built-in URL redirect feature in the admin (under Navigation or via the “URL Redirects” settings). If you change a product handle, Shopify often auto-prompts to create a redirect from the old to new. Use that to manage any manual redirects. Just be mindful, Shopify can’t redirect if the original URL is still active content (you must remove the page first).

- WordPress relies on plugins or server configuration for redirects. Popular plugins: Redirection (manage 301s easily), or Yoast Premium has a redirect manager. You can also edit the

.htaccesson Apache or use Nginx config if you’re comfortable. For large numbers of redirects (like thousands for a migration), sometimes it’s better to put them in the server config for performance. But plugins are fine for moderate amounts and ease of use.

Bulk Redirects and Regex: If you have pattern-based changes (like /blog/old-category/(.*) to /blog/new-category/$1), most redirect solutions support regex or wildcard redirects. This can save time. Just test thoroughly, as a wrong pattern could accidentally catch URLs you didn’t intend.

Monitoring After Redirects: After implementing, monitor Google Search Console for any crawl errors or sudden drop in indexed pages. Also monitor analytics – ideally the traffic should simply shift from old URLs to new. You might see temporary dips during the transition. Also, keep the redirects in place for the long term (at least several months to a year or more). If you remove a redirect too soon, Google might not have fully transferred signals, and old links out on the web could break.

UK-specific note: If you rebrand or change domain (perhaps dropping a .co.uk for a .com or vice versa), it’s a big move – consider timing (maybe not right before peak trading season). UK users are quite accustomed to .co.uk domains for local businesses; if switching to .com, reassure in messaging. But from pure SEO, as long as redirects are in place, you can maintain rankings. Also remember to update local citations and social profiles with the new URL.

In summary, redirects are your safety net and pathway for SEO continuity amid change. Use 301s for permanent moves to carry over your hard-earned SEO equity. Plan your redirect map carefully during any site changes. A well-implemented redirect strategy means users and search bots seamlessly reach the content even if URLs evolve.

XML Sitemaps

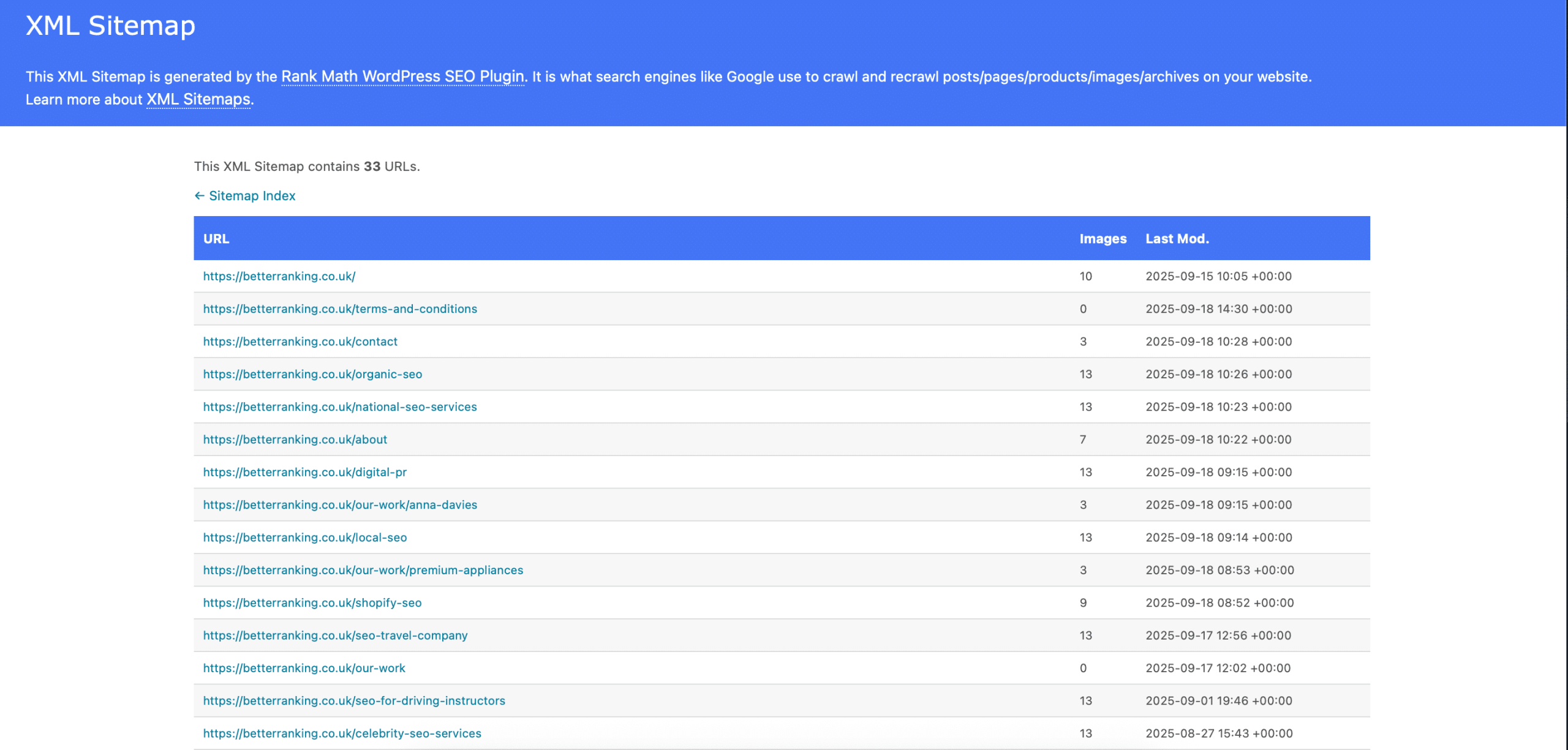

An XML sitemap is like a “menu” for search engine crawlers – it lists out the important URLs on your site that you want indexed. While a site that’s well-linked internally can often be crawled entirely without a sitemap, providing one can improve discovery, especially for large sites or new content. It’s a technical SEO staple to have an up-to-date XML sitemap for your site.

It’s an XML file (typically accessible at yourdomain.com/sitemap.xml) that lists URLs along with optional info like last modified date, change frequency, and priority. Search engines fetch this file to get hints about your site’s URLs. It doesn’t guarantee indexation, but it helps crawlers find pages that might be isolated or new. Google and Bing both consume sitemaps and allow sitemap upload on their Search Console and Webmaster Tools respectively. For a small UK business site with 20 pages, a sitemap isn’t critical, but it doesn’t hurt and is considered best practice.

Creating a Sitemap:

- WordPress: Plugins like Yoast SEO automatically generate a sitemap (usually at

/sitemap_index.xmlwith sub-sitemaps per post type). You just enable it and it updates whenever you publish or remove content. Other plugins like Google XML Sitemaps, or RankMath (SEO plugin) do similarly. - Shopify: Out of the box, Shopify generates a sitemap at

/sitemap.xmlwhich includes products, collections, pages, blog articles. It updates as you add/remove items. You don’t have to lift a finger; just know it’s there. - Other platforms might require a plugin or module. Alternatively, there are third-party tools that can crawl your site and create a sitemap for you, which you then upload.

What to Include: Generally, include all indexable pages that you care about. Do not include pages that are noindexed or blocked by robots.txt. For example, if you have a staging section disallowed by robots, exclude it from sitemap. Google may sometimes show a warning if your sitemap lists URLs that are noindex/blocked, as it’s a conflicting signal (“you told us about this URL but then disallowed/indexed it”). It’s not end-of-world, but better to keep it clean.

If your site is huge (over 50,000 URLs), split into multiple sitemap files, because that’s the limit per sitemap (50k URLs or 50MB file). For example, a large ecommerce might have sitemap_products1.xml, sitemap_products2.xml, etc. and a sitemap index listing those. Most CMS handle splitting automatically if needed.

Submit to Search Console: Once your sitemap exists, submit it in Google Search Console (and Bing Webmaster Tools). In GSC, under Index > Sitemaps, you can add the URL. GSC will show how many URLs were submitted and how many got indexed, and if there are any issues fetching it. This is a quick way to see if Google thinks some URLs are problematic (like “URL blocked by robots” errors).

Keep It Updated: The sitemap should auto-update when content changes (if using a CMS plugin). If manually maintained, remember to update it whenever you publish new pages or remove pages. The <lastmod> field in the sitemap can hint to Google when content changed, though Google doesn’t always strictly use it, it’s still good practice.

Priority and Changefreq: These fields can be included, but Google has said they largely ignore them. It doesn’t hurt to set them roughly correctly (like homepage high priority, updated daily content as daily etc.), but don’t worry too much. The URL list itself is the main useful part.

Images and Video Sitemaps: There are extensions to sitemaps where you can list images or videos for each URL. If image search SEO or video SEO is crucial (for say a photographer’s portfolio or a video site), consider using them. For most, a standard sitemap is fine; Google will find images on the page anyway when it crawls.

Localized Sitemaps: If you have separate sites or a multi-regional site, you can also incorporate hreflang info in sitemaps (as mentioned in the International SEO section). That’s an alternative to putting hreflang in HTML.

Orphan URLs: One nice thing about sitemaps is they can list URLs even if not yet linked anywhere (like a new landing page you haven’t linked in navigation). Google can then discover it. But note: if a URL is only in sitemap and not linked at all, Google might be suspicious (they prefer to find content via links). It may still index it though. Sitemaps are great for new sites or sections to get initial discovery.

Monitoring Indexing via Sitemap: After submission, check back on the status in Search Console periodically. If you see a lot of URLs not indexed, investigate why. Are they thin content? Duplicate? Or just new and Google is slow? The coverage report combined with sitemap info can guide you on what to improve for those pages (maybe add internal links or ensure no crawl blocks).

For UK businesses, one minor note: if you have a .co.uk site and a separate .com, and you use GSC, make sure to submit relevant sitemaps to each property. If you changed domain (like migrating UK site to a new domain), update the sitemap and submission accordingly.

In short, an XML sitemap is your way of handing search engines a list of pages you care about. It’s easy to set up and has potential benefits in faster and more complete indexation. It’s one of those “check the box” items in technical SEO that, while not guaranteeing anything, is certainly good hygiene and can only help, not hurt.

Robots.txt

The robots.txt file is a simple but powerful text file at the root of your site (yourdomain.com/robots.txt) that gives crawlers instructions on which URLs they can or cannot fetch. It’s often one of the first things search engine bots check when they visit your site. For technical SEO, properly configuring robots.txt can help manage crawl behavior, but a misconfiguration can also cause major SEO issues (e.g., accidental blocking of your whole site). Let’s delve into how to handle it correctly:

Robots.txt Basics: The file consists of rules targeting specific user-agents (bots). A simple example:

User-agent: *

Disallow: /admin/

Disallow: /cgi-bin/

Allow: /assets/

Sitemap: https://www.example.com/sitemap.xmlThis means “for all bots, don’t crawl anything under /admin/ or /cgi-bin/, but you’re explicitly allowed to crawl /assets/ (even if a parent directory was disallowed).” The sitemap line just provides the link to your sitemap.

Key points:

User-agent: *means all robots. You can also target specific bots likeUser-agent: Googlebotif needed for different directives.Disallow: /path/means do not crawl any URL that starts with that path. Note it’s prefix matching.Disallow: /foldercovers/folder/pageetc.- An empty Disallow means allow everything. Conversely, if you

Disallow:nothing (just blank), it means “no disallow path” which effectively means allowed. - There is no “Allow” needed unless a directory is disallowed and you want to let a subpart through. (E.g., disallow all of /private/, but allow /private/press-release/).

- Comments start with